# GEP-713: Metaresources and Policy Attachment

* Issue: [#713](https://github.com/kubernetes-sigs/gateway-api/issues/713)

* Status: Experimental

> **Note**: This GEP is exempt from the [Probationary Period][expprob] rules of

> our GEP overview as it existed before those rules did, and so it has been

> explicitly grandfathered in.

[expprob]:https://gateway-api.sigs.k8s.io/geps/overview/#probationary-period

## TLDR

This GEP aims to standardize terminology and processes around using one Kubernetes

object to modify the functions of one or more other objects.

This GEP defines some terms, firstly: _Metaresource_.

A Kubernetes object that _augments_ the behavior of an object

in a standard way is called a _Metaresource_.

This document proposes controlling the creation of configuration in the underlying

Gateway data plane using two types of Policy Attachment.

A "Policy Attachment" is a specific type of _metaresource_ that can affect specific

settings across either one object (this is "Direct Policy Attachment"), or objects

in a hierarchy (this is "Inherited Policy Attachment").

Individual policy APIs:

- must be their own CRDs (e.g. `TimeoutPolicy`, `RetryPolicy` etc),

- can be included in the Gateway API group and installation or be defined by

implementations

- and must include a common `TargetRef` struct in their specification to identify

how and where to apply that policy.

- _may_ include either a `defaults` section, an `overrides` section, or both. If

these are included, the Policy is an Inherited Policy, and should use the

inheritance rules defined in this document.

For Inherited Policies, this GEP also describes a set of expected behaviors

for how settings can flow across a defined hierarchy.

## Goals

* Establish a pattern for Policy resources which will be used for any policies

included in the Gateway API spec

* Establish a pattern for Policy attachment, whether Direct or Inherited,

which must be used for any implementation specific policies used with

Gateway API resources

* Provide a way to distinguish between required and default values for all

policy API implementations

* Enable policy attachment at all relevant scopes, including Gateways, Routes,

Backends, along with how values should flow across a hierarchy if necessary

* Ensure the policy attachment specification is generic and forward thinking

enough that it could be easily adapted to other grouping mechanisms like

Namespaces in the future

* Provide a means of attachment that works for both ingress and mesh

implementations of this API

* Provide a consistent specification that will ensure familiarity between both

included and implementation-specific policies so they can both be interpreted

the same way.

## Out of scope

* Define all potential policies that may be attached to resources

* Design the full structure and configuration of policies

## Background and concepts

When designing Gateway API, one of the things we’ve found is that we often need to be

able change the behavior of objects without being able to make changes to the spec

of those objects. Sometimes, this is because we can’t change the spec of the object

to hold the information we need ( ReferenceGrant, from

[GEP-709](https://gateway-api.sigs.k8s.io/geps/gep-709/), affecting Secrets

and Services is an example, as is Direct Policy Attachment), and sometimes it’s

because we want the behavior change to flow across multiple objects

(this is what Inherited Policy Attachment is for).

To put this another way, sometimes we need ways to be able to affect how an object

is interpreted in the API, without representing the description of those effects

inside the spec of the object.

This document describes the ways we design objects to meet these two use cases,

and why you might choose one or the other.

We use the term “metaresource” to describe the class of objects that _only_ augment

the behavior of another Kubernetes object, regardless of what they are targeting.

“Meta” here is used in its Greek sense of “more comprehensive”

or “transcending”, and “resource” rather than “object” because “metaresource”

is more pronounceable than “metaobject”. Additionally, a single word is better

than a phrase like “wrapper object” or “wrapper resource” overall, although both

of those terms are effectively synonymous with “metaresource”.

A "Policy Attachment" is a metaresource that affects the fields in existing objects

(like Gateway or Routes), or influences the configuration that's generated in an

underlying data plane.

"Direct Policy Attachment" is when a Policy object references a single object _only_,

and only modifies the fields of or the configuration associated with that object.

"Inherited Policy Attachment" is when a Policy object references a single object

_and any child objects of that object_ (according to some defined hierarchy), and

modifies fields of the child objects, or configuration associated with the child

objects.

In either case, a Policy may either affect an object by controlling the value

of one of the existing _fields_ in the `spec` of an object, or it may add

additional fields that are _not_ in the `spec` of the object.

### Direct Policy Attachment

A Direct Policy Attachment is tightly bound to one instance of a particular

Kind within a single namespace (or to an instance of a single Kind at cluster scope),

and only modifies the behavior of the object that matches its binding.

As an example, one use case that Gateway API currently does not support is how

to configure details of the TLS required to connect to a backend (in other words,

if the process running inside the backend workload expects TLS, not that some

automated infrastructure layer is provisioning TLS as in the Mesh case).

A hypothetical TLSConnectionPolicy that targets a Service could be used for this,

using the functionality of the Service as describing a set of endpoints. (It

should also be noted this is not the only way to solve this problem, just an

example to illustrate Direct Policy Attachment.)

The TLSConnectionPolicy would look something like this:

```yaml

apiVersion: gateway.networking.k8s.io/v1alpha2

kind: TLSConnectionPolicy

metadata:

name: tlsport8443

namespace: foo

spec:

targetRef: # This struct is defined as part of Gateway API

group: "" # Empty string means core - this is a standard convention

kind: Service

name: fooService

tls:

certificateAuthorityRefs:

- name: CAcert

port: 8443

```

All this does is tell an implementation, that for connecting to port `8443` on the

Service `fooService`, it should assume that the connection is TLS, and expect the

service's certificate to be validated by the chain in the `CAcert` Secret.

Importantly, this would apply to _every_ usage of that Service across any HTTPRoutes

in that namespace, which could be useful for a Service that is reused in a lot of

HTTPRoutes.

With these two examples in mind, here are some guidelines for when to consider

using Direct Policy Attachment:

* The number or scope of objects to be modified is limited or singular. Direct

Policy Attachments must target one specific object.

* The modifications to be made to the objects don’t have any transitive information -

that is, the modifications only affect the single object that the targeted

metaresource is bound to, and don’t have ramifications that flow beyond that

object.

* In terms of status, it should be reasonably easy for a user to understand that

everything is working - basically, as long as the targeted object exists, and

the modifications are valid, the metaresource is valid, and this should be

straightforward to communicate in one or two Conditions. Note that at the time

of writing, this is *not* completed.

* Direct Policy Attachment _should_ only be used to target objects in the same

namespace as the Policy object. Allowing cross-namespace references brings in

significant security concerns, and/or difficulties about merging cross-namespace

policy objects. Notably, Mesh use cases may need to do something like this for

consumer policies, but in general, Policy objects that modify the behavior of

things outside their own namespace should be avoided unless it uses a handshake

of some sort, where the things outside the namespace can opt–out of the behavior.

(Notably, this is the design that we used for ReferenceGrant).

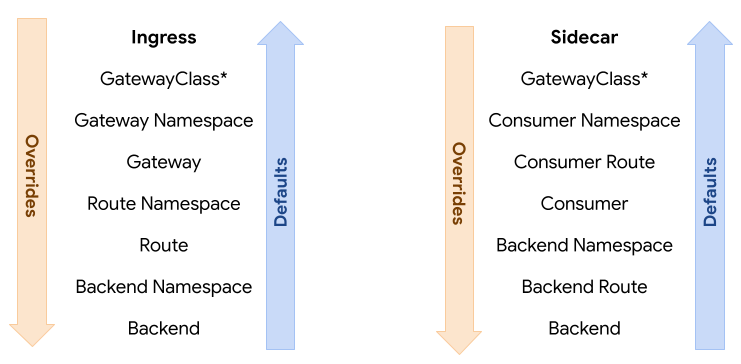

### Inherited Policy Attachment: It's all about the defaults and overrides

Because a Inherited Policy is a metaresource, it targets some other resource

and _augments_ its behavior.

But why have this distinct from other types of metaresource? Because Inherited

Policy resources are designed to have a way for settings to flow down a hierarchy.

Defaults set the default value for something, and can be overridden by the

“lower” objects (like a connection timeout default policy on a Gateway being

overridable inside a HTTPRoute), and Overrides cannot be overridden by “lower”

objects (like setting a maximum client timeout to some non-infinite value at the

Gateway level to stop HTTPRoute owners from leaking connections over time).

Here are some guidelines for when to consider using a Inherited Policy object:

* The settings or configuration are bound to one containing object, but affect

other objects attached to that one (for example, affecting HTTPRoutes attached

to a single Gateway, or all HTTPRoutes in a GatewayClass).

* The settings need to able to be defaulted, but can be overridden on a per-object

basis.

* The settings must be enforced by one persona, and not modifiable or removable

by a lesser-privileged persona. (The owner of a GatewayClass may want to restrict

something about all Gateways in a GatewayClass, regardless of who owns the Gateway,

or a Gateway owner may want to enforce some setting across all attached HTTPRoutes).

* In terms of status, a good accounting for how to record that the Policy is

attached is easy, but recording what resources the Policy is being applied to

is not, and needs to be carefully designed to avoid fanout apiserver load.

(This is not built at all in the current design either).

When multiple Inherited Policies are used, they can interact in various ways,

which are governed by the following rules, which will be expanded on later in this document.

* If a Policy does not affect an object's fields directly, then the resultant

Policy should be the set of all distinct fields inside the relevant Policy objects,

as set out by the rules below.

* For Policies that affect an object's existing fields, multiple instances of the

same Policy Kind affecting an object's fields will be evaluated as

though only a single Policy "wins" the right to affect each field. This operation

is performed on a _per-distinct-field_ basis.

* Settings in `overrides` stanzas will win over the same setting in a `defaults`

stanza.

* `overrides` settings operate in a "less specific beats more specific" fashion -

Policies attached _higher_ up the hierarchy will beat the same type of Policy

attached further down the hierarchy.

* `defaults` settings operate in a "more specific beats less specific" fashion -

Policies attached _lower down_ the hierarchy will beat the same type of Policy

attached further _up_ the hierarchy.

* For `defaults`, the _most specific_ value is the one _inside the object_ that

the Policy applies to; that is, if a Policy specifies a `default`, and an object

specifies a value, the _object's_ value will win.

* Policies interact with the fields they are controlling in a "replace value"

fashion.

* For fields where the `value` is a scalar, (like a string or a number)

should have their value _replaced_ by the value in the Policy if it wins.

Notably, this means that a `default` will only ever replace an empty or unset

value in an object.

* For fields where the value is an object, the Policy should include the fields

in the object in its definition, so that the replacement can be on simple fields

rather than complex ones.

* For fields where the final value is non-scalar, but is not an _object_ with

fields of its own, the value should be entirely replaced, _not_ merged. This

means that lists of strings or lists of ints specified in a Policy will overwrite

the empty list (in the case of a `default`) or any specified list (in the case

of an `override`). The same applies to `map[string]string` fields. An example

here would be a field that stores a map of annotations - specifying a Policy

that overrides annotations will mean that a final object specifying those

annotations will have its value _entirely replaced_ by an `override` setting.

* In the case that two Policies of the same type specify different fields, then

_all_ of the specified fields should take effect on the affected object.

Examples to further illustrate these rules are given below.

## Naming Policy objects

The preceding rules discuss how Policy objects should _behave_, but this section

describes how Policy objects should be _named_.

Policy objects should be clearly named so as to indicate that they are Policy

metaresources.

The simplest way to do that is to ensure that the type's name contains the `Policy`

string.

Implementations _should_ use `Policy` as the last part of the names of object types

that use this pattern.

If an implementation does not, then they _must_ clearly document what objects

are Policy metaresources in their documentation. Again, this is _not recommended_

without a _very_ good reason.

## Policy Attachment examples and behavior

This approach is building on concepts from all of the alternatives discussed

below. This is very similar to the (now removed) BackendPolicy resource in the API,

but also borrows some concepts from the [ServicePolicy

proposal](https://github.com/kubernetes-sigs/gateway-api/issues/611).

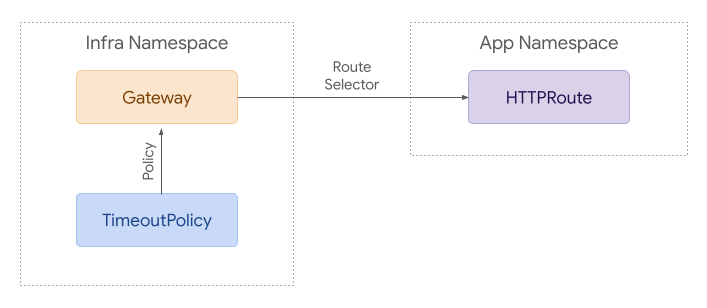

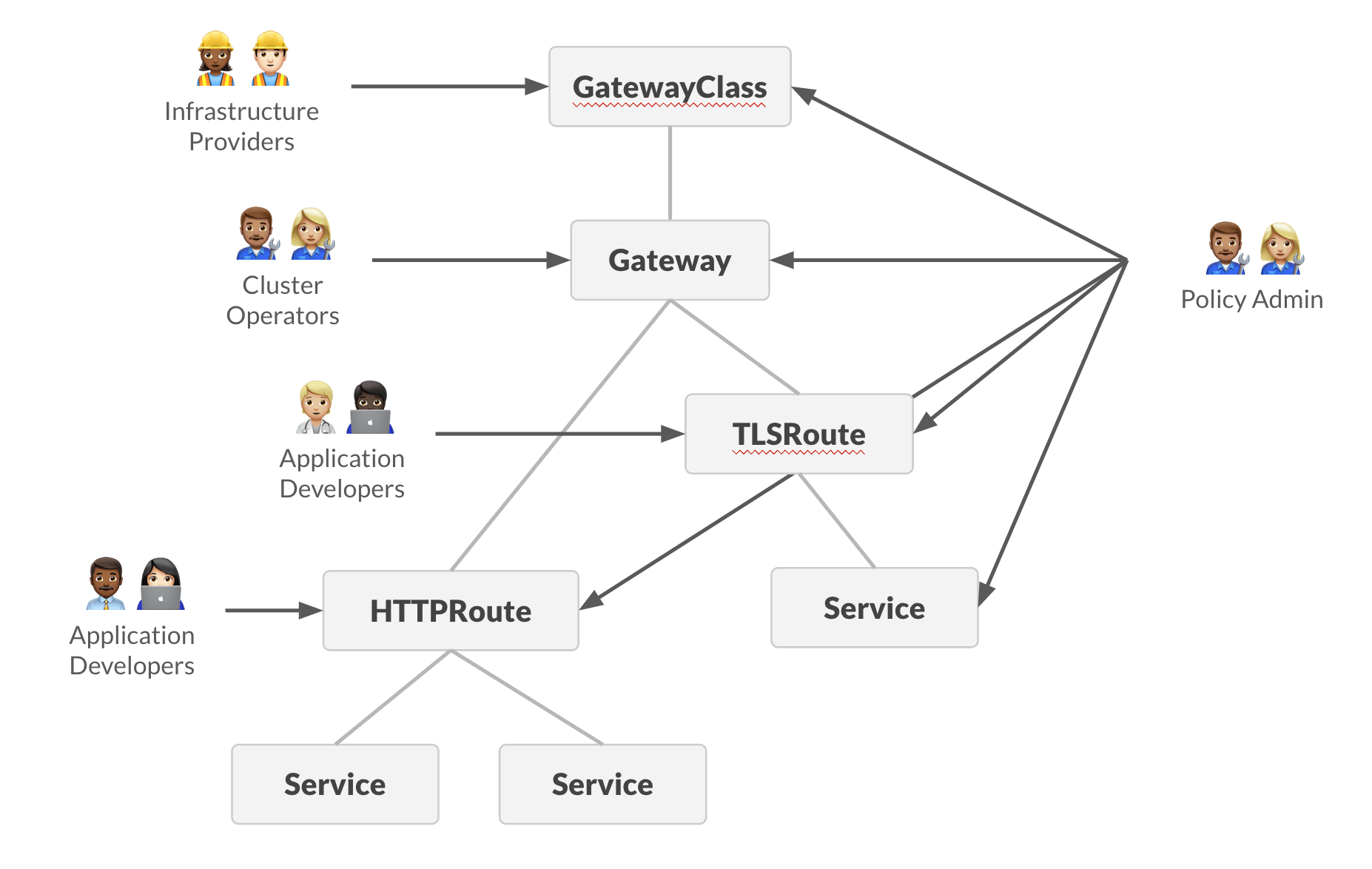

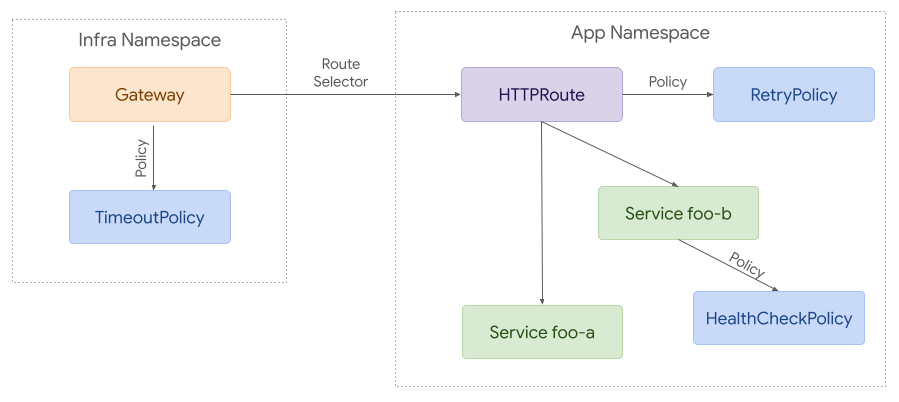

### Policy Attachment for Ingress

Attaching a Directly Attached Policy to Gateway resources for ingress use cases

is relatively straightforward. A policy can reference the resource it wants to

apply to.

Access is granted with RBAC - anyone that has access to create a RetryPolicy in

a given namespace can attach it to any resource within that namespace.

An Inherited Policy can attach to a parent resource, and then each policy

applies to the referenced resource and everything below it in terms of hierarchy.

Although this example is likely more complex than many real world

use cases, it helps demonstrate how policy attachment can work across

namespaces.

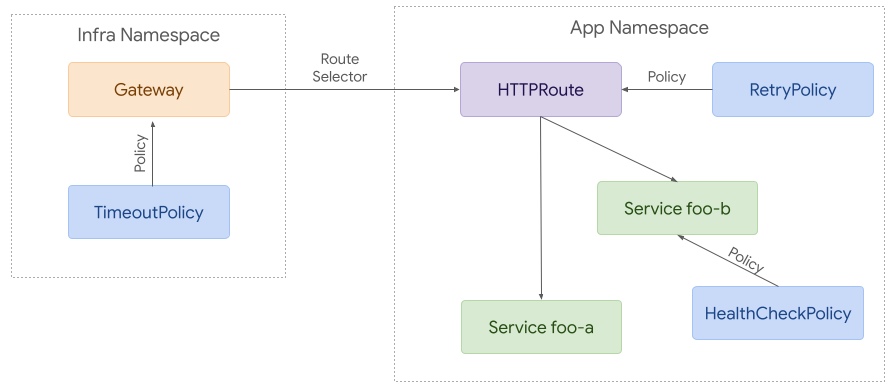

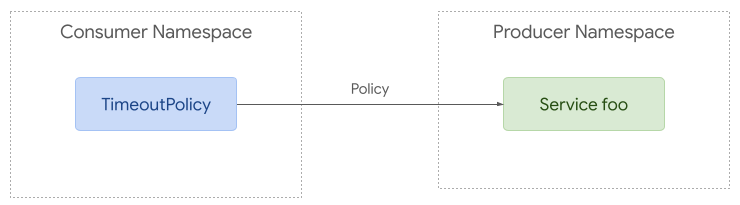

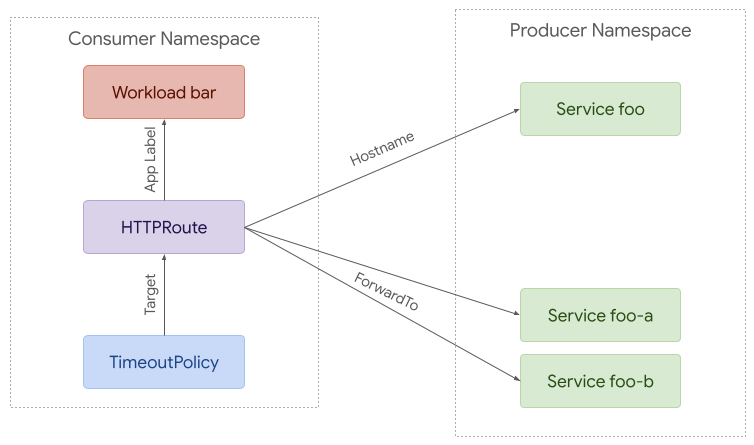

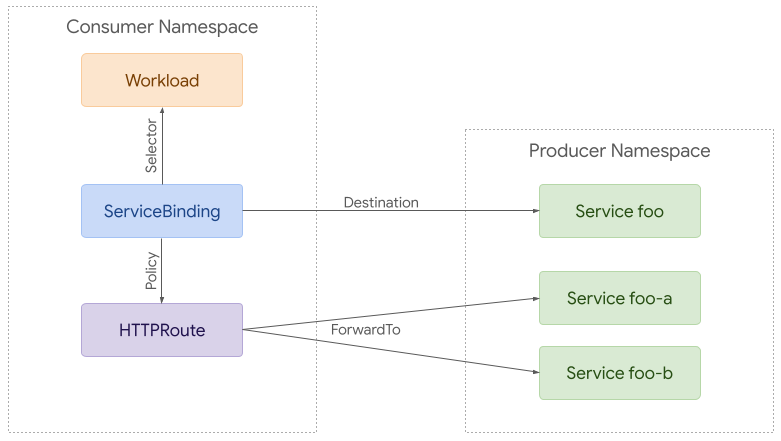

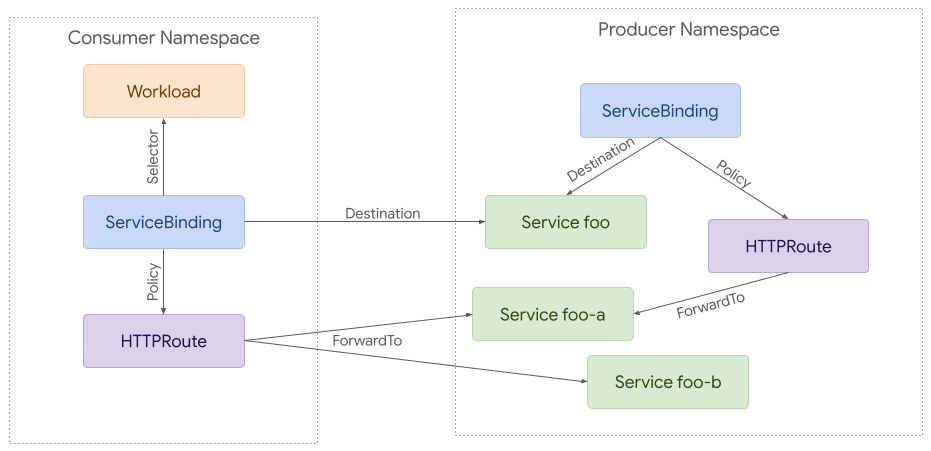

### Policy Attachment for Mesh

Although there is a great deal of overlap between ingress and mesh use cases,

mesh enables more complex policy attachment scenarios. For example, you may want

to apply policy to requests from a specific namespace to a backend in another

namespace.

Policy attachment can be quite simple with mesh. Policy can be applied to any

resource in any namespace but it can only apply to requests from the same

namespace if the target is in a different namespace.

At the other extreme, policy can be used to apply to requests from a specific

workload to a backend in another namespace. A route can be used to intercept

these requests and split them between different backends (foo-a and foo-b in

this case).

### Policy TargetRef API

Each Policy resource MUST include a single `targetRef` field. It must not

target more than one resource at a time, but it can be used to target larger

resources such as Gateways or Namespaces that may apply to multiple child

resources.

As with most APIs, there are countless ways we could choose to expand this in

the future. This includes supporting multiple targetRefs and/or label selectors.

Although this would enable compelling functionality, it would increase the

complexity of an already complex API and potentially result in more conflicts

between policies. Although we may choose to expand the targeting capabilities

in the future, at this point it is strongly preferred to start with a simpler

pattern that still leaves room for future expansion.

The `targetRef` field MUST have the following structure:

```go

// PolicyTargetReference identifies an API object to apply policy to.

type PolicyTargetReference struct {

// Group is the group of the target resource.

//

// +kubebuilder:validation:MinLength=1

// +kubebuilder:validation:MaxLength=253

Group string `json:"group"`

// Kind is kind of the target resource.

//

// +kubebuilder:validation:MinLength=1

// +kubebuilder:validation:MaxLength=253

Kind string `json:"kind"`

// Name is the name of the target resource.

//

// +kubebuilder:validation:MinLength=1

// +kubebuilder:validation:MaxLength=253

Name string `json:"name"`

// Namespace is the namespace of the referent. When unspecified, the local

// namespace is inferred. Even when policy targets a resource in a different

// namespace, it may only apply to traffic originating from the same

// namespace as the policy.

//

// +kubebuilder:validation:MinLength=1

// +kubebuilder:validation:MaxLength=253

// +optional

Namespace string `json:"namespace,omitempty"`

}

```

### Sample Policy API

The following structure can be used as a starting point for any Policy resource

using this API pattern. Note that the PolicyTargetReference struct defined above

will be distributed as part of the Gateway API.

```go

// ACMEServicePolicy provides a way to apply Service policy configuration with

// the ACME implementation of the Gateway API.

type ACMEServicePolicy struct {

metav1.TypeMeta `json:",inline"`

metav1.ObjectMeta `json:"metadata,omitempty"`

// Spec defines the desired state of ACMEServicePolicy.

Spec ACMEServicePolicySpec `json:"spec"`

// Status defines the current state of ACMEServicePolicy.

Status ACMEServicePolicyStatus `json:"status,omitempty"`

}

// ACMEServicePolicySpec defines the desired state of ACMEServicePolicy.

type ACMEServicePolicySpec struct {

// TargetRef identifies an API object to apply policy to.

TargetRef gatewayv1a2.PolicyTargetReference `json:"targetRef"`

// Override defines policy configuration that should override policy

// configuration attached below the targeted resource in the hierarchy.

// +optional

Override *ACMEPolicyConfig `json:"override,omitempty"`

// Default defines default policy configuration for the targeted resource.

// +optional

Default *ACMEPolicyConfig `json:"default,omitempty"`

}

// ACMEPolicyConfig contains ACME policy configuration.

type ACMEPolicyConfig struct {

// Add configurable policy here

}

// ACMEServicePolicyStatus defines the observed state of ACMEServicePolicy.

type ACMEServicePolicyStatus struct {

// Conditions describe the current conditions of the ACMEServicePolicy.

//

// +optional

// +listType=map

// +listMapKey=type

// +kubebuilder:validation:MaxItems=8

Conditions []metav1.Condition `json:"conditions,omitempty"`

}

```

### Hierarchy

Each policy MAY include default or override values. Default values are given

precedence from the bottom up, while override values are top down. That means

that a default attached to a Backend will have the highest precedence among

default values while an override value attached to a GatewayClass will have the

highest precedence overall.

To illustrate this, consider 3 resources with the following hierarchy:

A > B > C. When attaching the concept of defaults and overrides to that, the

hierarchy would be expanded to this:

A override > B override > C override > C default > B default > A default.

Note that the hierarchy is reversed for defaults. The rationale here is that

overrides usually need to be enforced top down while defaults should apply to

the lowest resource first. For example, if an admin needs to attach required

policy, they can attach it as an override to a Gateway. That would have

precedence over Routes and Services below it. On the other hand, an app owner

may want to set a default timeout for their Service. That would have precedence

over defaults attached at higher levels such as Route or Gateway.

If using defaults _and_ overrides, each policy resource MUST include 2 structs

within the spec. One with override values and the other with default values.

In the following example, the policy attached to the Gateway requires cdn to

be enabled and provides some default configuration for that. The policy attached

to the Route changes the value for one of those fields (includeQueryString).

```yaml

kind: CDNCachingPolicy # Example of implementation specific policy name

spec:

override:

cdn:

enabled: true

default:

cdn:

cachePolicy:

includeHost: true

includeProtocol: true

includeQueryString: true

targetRef:

kind: Gateway

name: example

---

kind: CDNCachingPolicy

spec:

default:

cdn:

cachePolicy:

includeQueryString: false

targetRef:

type: direct

kind: HTTPRoute

name: example

```

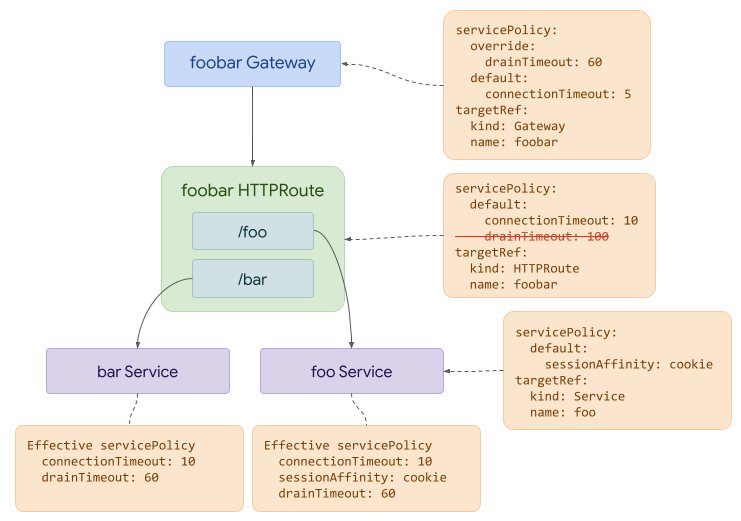

In this final example, we can see how the override attached to the Gateway has

precedence over the default drainTimeout value attached to the Route. At the

same time, we can see that the default connectionTimeout attached to the Route

has precedence over the default attached to the Gateway.

Also note how the different resources interact - fields that are not common across

objects _may_ both end up affecting the final object.

#### Supported Resources

It is important to note that not every implementation will be able to support

policy attachment to each resource described in the hierarchy above. When that

is the case, implementations MUST clearly document which resources a policy may

be attached to.

#### Attaching Policy to GatewayClass

GatewayClass may be the trickiest resource to attach policy to. Policy

attachment relies on the policy being defined within the same scope as the

target. This ensures that only users with write access to a policy resource in a

given scope will be able to modify policy at that level. Since GatewayClass is a

cluster scoped resource, this means that any policy attached to it must also be

cluster scoped.

GatewayClass parameters provide an alternative to policy attachment that may be

easier for some implementations to support. These parameters can similarly be

used to set defaults and requirements for an entire GatewayClass.

### Targeting External Services

In some cases (likely limited to mesh) we may want to apply policies to requests

to external services. To accomplish this, implementations can choose to support

a reference to a virtual resource type:

```yaml

apiVersion: networking.acme.io/v1alpha1

kind: RetryPolicy

metadata:

name: foo

spec:

default:

maxRetries: 5

targetRef:

group: networking.acme.io

kind: ExternalService

name: foo.com

```

### Merging into existing `spec` fields

It's possible (even likely) that configuration in a Policy may need to be merged

into an existing object's fields somehow, particularly for Inherited policies.

When merging into an existing fields inside an object, Policy objects should

merge values at a scalar level, not at a struct or object level.

For example, in the `CDNCachingPolicy` example above, the `cdn` struct contains

a `cachePolicy` struct that contains fields. If an implementation was merging

this configuration into an existing object that contained the same fields, it

should merge the fields at a scalar level, with the `includeHost`,

`includeProtocol`, and `includeQueryString` values being defaulted if they were

not specified in the object being controlled. Similarly, for `overrides`, the

values of the innermost scalar fields should overwrite the scalar fields in the

affected object.

Implementations should not copy any structs from the Policy object directly into the

affected object, any fields that _are_ overridden should be overridden on a per-field

basis.

In the case that the field in the Policy affects a struct that is a member of a list,

each existing item in the list in the affected object should have each of its

fields compared to the corresponding fields in the Policy.

For non-scalar field _values_, like a list of strings, or a `map[string]string`

value, the _entire value_ must be overwritten by the value from the Policy. No

merging should take place. This mainly applies to `overrides`, since for

`defaults`, there should be no value present in a field on the final object.

This table shows how this works for various types:

|Type|Object config|Override Policy config|Result|

|----|-------------|----------------------|------|

|string| `key: "foo"` | `key: "bar"` | `key: "bar"` |

|list| `key: ["a","b"]` | `key: ["c","d"]` | `key: ["c","d"]` |

|`map[string]string`| `key: {"foo": "a", "bar": "b"}` | `key: {"foo": "c", "bar": "d"}` | `key: {"foo": "c", "bar": "d"}` |

### Conflict Resolution

It is possible for multiple policies to target the same object _and_ the same

fields inside that object. If multiple policy resources target

the same resource _and_ have an identical field specified with different values,

precedence MUST be determined in order of the following criteria, continuing on

ties:

* Direct Policies override Inherited Policies. If preventing settings from

being overwritten is important, implementations should only use Inherited

Policies, and the `override` stanza that implies. Note also that it's not

intended that Direct and Inherited Policies should overlap, so this should

only come up in exceptional circumstances.

* Inside Inherited Policies, the same setting in `overrides` beats the one in

`defaults`.

* The oldest Policy based on creation timestamp. For example, a Policy with a

creation timestamp of "2021-07-15 01:02:03" is given precedence over a Policy

with a creation timestamp of "2021-07-15 01:02:04".

* The Policy appearing first in alphabetical order by `{namespace}/{name}`. For

example, foo/bar is given precedence over foo/baz.

For a better user experience, a validating webhook can be implemented to prevent

these kinds of conflicts all together.

## Status and the Discoverability Problem

So far, this document has talked about what Policy Attachment is, different types

of attachment, and how those attachments work.

Probably the biggest impediment to this GEP moving forward is the discoverability

problem; that is, it’s critical that an object owner be able to know what policy

is affecting their object, and ideally its contents.

To understand this a bit better, let’s consider this parable, with thanks to Flynn:

### The Parable

It's a sunny Wednesday afternoon, and the lead microservices developer for

Evil Genius Cupcakes is windsurfing. Work has been eating Ana alive for the

past two and a half weeks, but after successfully deploying version 3.6.0 of

the `baker` service this morning, she's escaped early to try to unwind a bit.

Her shoulders are just starting to unknot when her phone pings with a text

from Charlie, down in the NOC. Waterproof phones are a blessing, but also a

curse.

**Charlie**: _Hey Ana. Things are still running, more or less, but latencies

on everything in the `baker` namespace are crazy high after your last rollout,

and `baker` itself has a weirdly high load. Sorry to interrupt you on the lake

but can you take a look? Thanks!!_

Ana stares at the phone for a long moment, heart sinking, then sighs and

turns back to shore.

What she finds when dries off and grabs her laptop is strange. `baker` does

seem to be taking much more load than its clients are sending, and its clients

report much higher latencies than they’d expect. She doublechecks the

Deployment, the Service, and all the HTTPRoutes around `baker`; everything

looks good. `baker`’s logs show her mostly failed requests... with a lot of

duplicates? Ana checks her HTTPRoute again, though she's pretty sure you

can't configure retries there, and finds nothing. But it definitely looks like

clients are retrying when they shouldn’t be.

She pings Charlie.

**Ana**: _Hey Charlie. Something weird is up, looks like requests to `baker`

are failing but getting retried??_

A minute later they answer.

**Charlie**: 🤷 _Did you configure retries?_

**Ana**: _Dude. I don’t even know how to._ 😂

**Charlie**: _You just attach a RetryPolicy to your HTTPRoute._

**Ana**: _Nope. Definitely didn’t do that._

She types `kubectl get retrypolicy -n baker` and gets a permission error.

**Ana**: _Huh, I actually don’t have permissions for RetryPolicy._ 🤔

**Charlie**: 🤷 _Feels like you should but OK, guess that can’t be it._

Minutes pass while both look at logs.

**Charlie**: _I’m an idiot. There’s a RetryPolicy for the whole namespace –

sorry, too many policies in the dashboard and I missed it. Deleting that since

you don’t want retries._

**Ana**: _Are you sure that’s a good–_

Ana’s phone shrills while she’s typing, and she drops it. When she picks it

up again she sees a stack of alerts. She goes pale as she quickly flips

through them: there’s one for every single service in the `baker` namespace.

**Ana**: _PUT IT BACK!!_

**Charlie**: _Just did. Be glad you couldn't hear all the alarms here._ 😕

**Ana**: _What the hell just happened??_

**Charlie**: _At a guess, all the workloads in the `baker` namespace actually

fail a lot, but they seem OK because there are retries across the whole

namespace?_ 🤔

Ana's blood runs cold.

**Charlie**: _Yeah. Looking a little closer, I think your `baker` rollout this

morning would have failed without those retries._ 😕

There is a pause while Ana's mind races through increasingly unpleasant

possibilities.

**Ana**: _I don't even know where to start here. How long did that

RetryPolicy go in? Is it the only thing like it?_

**Charlie**: _Didn’t look closely before deleting it, but I think it said a few

months ago. And there are lots of different kinds of policy and lots of

individual policies, hang on a minute..._

**Charlie**: _Looks like about 47 for your chunk of the world, a couple hundred

system-wide._

**Ana**: 😱 _Can you tell me what they’re doing for each of our services? I

can’t even_ look _at these things._ 😕

**Charlie**: _That's gonna take awhile. Our tooling to show us which policies

bind to a given workload doesn't go the other direction._

**Ana**: _...wait. You have to_ build tools _to know if retries are turned on??_

Pause.

**Charlie**: _Policy attachment is more complex than we’d like, yeah._ 😐

_Look, how ‘bout roll back your `baker` change for now? We can get together in

the morning and start sorting this out._

Ana shakes her head and rolls back her edits to the `baker` Deployment, then

sits looking out over the lake as the deployment progresses.

**Ana**: _Done. Are things happier now?_

**Charlie**: _Looks like, thanks. Reckon you can get back to your sailboard._ 🙂

Ana sighs.

**Ana**: _Wish I could. Wind’s died down, though, and it'll be dark soon.

Just gonna head home._

**Charlie**: _Ouch. Sorry to hear that._ 😐

One more look out at the lake.

**Ana**: _Thanks for the help. Wish we’d found better answers._ 😢

### The Problem, restated

What this parable makes clear is that, in the absence of information about what

Policy is affecting an object, it’s very easy to make poor decisions.

It’s critical that this proposal solve the problem of showing up to three things,

listed in increasing order of desirability:

- _That_ some Policy is affecting a particular object

- _Which_ Policy is (or Policies are) affecting a particular object

- _What_ settings in the Policy are affecting the object.

In the parable, if Ana and Charlie had known that there were Policies affecting

the relevant object, then they could have gone looking for the relevant Policies

and things would have played out differently. If they knew which Policies, they

would need to look less hard, and if they knew what the settings being applied

were, then the parable would have been able to be very short indeed.

(There’s also another use case to consider, in that Charlie should have been able

to see that the Policy on the namespace was in use in many places before deleting

it.)

To put this another way, Policy Attachment is effectively adding a fourth Persona,

the Policy Admin, to Gateway API’s persona list, and without a solution to the

discoverability problem, their actions are largely invisible to the Application

Developer. Not only that, but their concerns cut across the previously established

levels.

From the Policy Admin’s point of view, they need to know across their whole remit

(which conceivably could be the whole cluster):

- _What_ Policy has been created

- _Where_ it’s applied

- _What_ the resultant policy is saying

Which again, come down to discoverability, and can probably be addressed in similar

ways at an API level to the Application Developer's concerns.

An important note here is that a key piece of information for Policy Admins and

Cluster Operators is “How many things does this Policy affect?”. In the parable,

this would have enabled Charlie to know that deleting the Namespace Policy would

affect many other people than just Ana.

### Problems we need to solve

Before we can get into solutions, we need to discuss the problems that solutions

may need to solve, so that we have some criteria for evaluating those solutions.

#### User discoverability

Let's go through the various users of Gateway API and what they need to know about

Policy Attachment.

In all of these cases, we should aim to keep the troubleshooting distance low;

that is, that there should be a minimum of hops required between objects from the

one owned by the user to the one responsible for a setting.

Another way to think of the troubleshooting distance in this context is "How many

`kubectl` commands would the user need to do to understand that a Policy is relevant,

which Policy is relevant, and what configuration the full set of Policy is setting?"

##### Application Developer Discoverability

How does Ana, or any Application Developer who owns one or more Route objects know

that their object is affected by Policy, which Policy is affecting it, and what

the content of the Policy is?

The best outcome is that Ana needs to look only at a specific route to know what

Policy settings are being applied to that Route, and where they come from.

However, some of the other problems below make it very difficult to achieve this.

##### Policy Admin Discoverability

How does the Policy Admin know what Policy is applied where, and what the content

of that Policy is?

How do they validate that Policy is being used in ways acceptable to their organization?

For any given Policy object, how do they know how many places it's being used?

##### Cluster Admin Discoverability

The Cluster Admin has similar concerns to the Policy Admin, but with a focus on

being able to determine what's relevant when something is broken.

How does the Cluster Admin know what Policy is applied where, and what the content

of that Policy is?

For any given Policy object, how do they know how many places it's being used?

#### Evaluating and Displaying Resultant Policy

For any given Policy type, whether Direct Attached or Inherited, implementations

will need to be able to _calculate_ the resultant set of Policy to be able to

apply that Policy to the correct parts of their data plane configuration.

However, _displaying_ that resultant set of Policy in a way that is straightforward

for the various personas to consume is much harder.

The easiest possible option for Application Developers would be for the

implementation to make the full resultant set of Policy available in the status

of objects that the Policy affects. However, this runs into a few problems:

- The status needs to be namespaced by the implementation

- The status could get large if there are a lot of Policy objects affecting an

object

- Building a common data representation pattern that can fit into a single common

schema is not straightforward.

- Updating one Policy object could cause many affected objects to need to be

updated themselves. This sort of fan-out problem can be very bad for apiserver

load, particularly if Policy changes rapidly, there are a lot of objects, or both.

##### Status needs to be namespaced by implementation

Because an object can be affected by multiple implementations at once, any status

we add must be namespaced by the implementation.

In Route Parent status, we've used the parentRef plus the controller name for this.

For Policy, we can do something similar and namespace by the reference to the

implementation's controller name.

We can't easily namespace by the originating Policy because the source could be

more than one Policy object.

##### Creating common data representation patterns

The problem here is that we need to have a _common_ pattern for including the

details of an _arbitrarily defined_ object, that needs to be included in the base

API.

So we can't use structured data, because we have no way of knowing what the

structure will be beforehand.

This suggests that we need to use unstructured data for representing the main

body of an arbitrary Policy object.

Practically, this will need to be a string representation of the YAML form of the

body of the Policy object (absent the metadata part of every Kubernetes object).

Policy Attachment does not mandate anything about the design of the object's top

level except that it must be a Kubernetes object, so the only thing we can rely

on is the presence of the Kubernetes metadata elements: `apiVersion`, `kind`,

and `metadata`.

A string representation of the rest of the file is the best we can do here.

##### Fanout status update problems

The fanout problem is that, when an update takes place in a single object (a

Policy, or an object with a Policy attached), an implementation may need to

update _many_ objects if it needs to place details of what Policy applies, or

what the resultant set of policy is on _every_ object.

Historically, this is a risky strategy and needs to be carefully applied, as

it's an excellent way to create apiserver load problems, which can produce a large

range of bad effects for cluster stability.

This does not mean that we can't do anything at all that affects multiple objects,

but that we need to carefully consider what information is stored in status so

that _every_ Policy update does not require a status update.

#### Solution summary

Because Policy Attachment is a pattern for APIs, not an API, and needs to address

all the problems above, the strategy this GEP proposes is to define a range of

options for increasing the discoverabilty of Policy resources, and provide

guidelines for when they should be used.

It's likely that at some stage, the Gateway API CRDs will include some Policy

resources, and these will be designed with all these discoverabiity solutions

in mind.

### Solution cookbook

This section contains some required patterns for Policy objects and some

suggestions. Each will be marked as MUST, SHOULD, or MAY, using the standard

meanings of those terms.

Additionally, the status of each solution is noted at the beginning of the section.

#### Standard label on CRD objects

Status: Required

Each CRD that defines a Policy object MUST include a label that specifies that

it is a Policy object, and that label MUST specify the _type_ of Policy attachment

in use.

The label is `gateway.networking.k8s.io/policy: inherited|direct`.

This solution is intended to allow both users and tooling to identify which CRDs

in the cluster should be treated as Policy objects, and so is intended to help

with discoverability generally. It will also be used by the forthcoming `kubectl`

plugin.

##### Design considerations

This is already part of the API pattern, but is being lifted to more prominience

here.

#### Standard status struct

Status: Experimental

Policy objects SHOULD use the upstream `PolicyAncestorStatus` struct in their respective

Status structs. Please see the included `PolicyAncestorStatus` struct, and its use in

the `BackendTLSPolicy` object for detailed examples. Included here is a representative

version.

This pattern enables different conditions to be set for different "Ancestors"

of the target resource. This is particularly helpful for policies that may be

implemented by multiple controllers or attached to resources with different

capabilities. This pattern also provides a clear view of what resources a

policy is affecting.

For the best integration with community tooling and consistency across

the broader community, we recommend that all implementations transition

to Policy status with this kind of nested structure.

This is an `Ancestor` status rather than a `Parent` status, as in the Route status

because for Policy attachment, the relevant object may or may not be the direct

parent.

For example, `BackendTLSPolicy` directly attaches to a Service, which may be included

in multiple Routes, in multiple Gateways. However, for many implementations,

the status of the `BackendTLSPolicy` will be different only at the Gateway level,

so Gateway is the relevant Ancestor for the status.

Each Gateway that has a Route that includes a backend with an attached `BackendTLSPolicy`

MUST have a separate `PolicyAncestorStatus` section in the `BackendTLSPolicy`'s

`status.ancestors` stanza, which mandates that entries must be distinct using the

combination of the `AncestorRef` and the `ControllerName` fields as a key.

See [GEP-1897][gep-1897] for the exact details.

[gep-1897]: /geps/gep-1897

```go

// PolicyAncestorStatus describes the status of a route with respect to an

// associated Ancestor.

//

// Ancestors refer to objects that are either the Target of a policy or above it in terms

// of object hierarchy. For example, if a policy targets a Service, an Ancestor could be

// a Route or a Gateway.

// In the context of policy attachment, the Ancestor is used to distinguish which

// resource results in a distinct application of this policy. For example, if a policy

// targets a Service, it may have a distinct result per attached Gateway.

//

// Policies targeting the same resource may have different effects depending on the

// ancestors of those resources. For example, different Gateways targeting the same

// Service may have different capabilities, especially if they have different underlying

// implementations.

//

// For example, in BackendTLSPolicy, the Policy attaches to a Service that is

// used as a backend in a HTTPRoute that is itself attached to a Gateway.

// In this case, the relevant object for status is the Gateway, and that is the

// ancestor object referred to in this status.

//

// Note that a Target of a Policy is also a valid Ancestor, so for objects where

// the Target is the relevant object for status, this struct SHOULD still be used.

type PolicyAncestorStatus struct {

// AncestorRef corresponds with a ParentRef in the spec that this

// RouteParentStatus struct describes the status of.

AncestorRef ParentReference `json:"ancestorRef"`

// ControllerName is a domain/path string that indicates the name of the

// controller that wrote this status. This corresponds with the

// controllerName field on GatewayClass.

//

// Example: "example.net/gateway-controller".

//

// The format of this field is DOMAIN "/" PATH, where DOMAIN and PATH are

// valid Kubernetes names

// (https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/overview/working-with-objects/names/#names).

//

// Controllers MUST populate this field when writing status. Controllers should ensure that

// entries to status populated with their ControllerName are cleaned up when they are no

// longer necessary.

ControllerName GatewayController `json:"controllerName"`

// Conditions describes the status of the Policy with respect to the given Ancestor.

//

// +listType=map

// +listMapKey=type

// +kubebuilder:validation:MinItems=1

// +kubebuilder:validation:MaxItems=8

Conditions []metav1.Condition `json:"conditions,omitempty"`

}

// PolicyStatus defines the common attributes that all Policies SHOULD include

// within their status.

type PolicyStatus struct {

// Ancestors is a list of ancestor resources (usually Gateways) that are

// associated with the route, and the status of the route with respect to

// each ancestor. When this route attaches to a parent, the controller that

// manages the parent and the ancestors MUST add an entry to this list when

// the controller first sees the route and SHOULD update the entry as

// appropriate when the relevant ancestor is modified.

//

// Note that choosing the relevant ancestor is left to the Policy designers;

// an important part of Policy design is designing the right object level at

// which to namespace this status.

//

// Note also that implementations MUST ONLY populate ancestor status for

// the Ancestor resources they are responsible for. Implementations MUST

// use the ControllerName field to uniquely identify the entries in this list

// that they are responsible for.

//

// A maximum of 32 ancestors will be represented in this list. An empty list

// means the Policy is not relevant for any ancestors.

//

// +kubebuilder:validation:MaxItems=32

Ancestors []PolicyAncestorStatus `json:"ancestors"`

}

```

##### Design considerations

This is recommended as the base for Policy object's status. As Policy Attachment

is a pattern, not an API, "recommended" is the strongest we can make this, but

we believe that standardizing this will help a lot with discoverability.

Note that is likely that all Gateway API tooling will expect policy status to follow

this structure. To benefit from broader consistency and discoverability, we

recommend transitioning to this structure for all Gateway API Policies.

#### Standard status Condition on Policy-affected objects

Support: Provisional

This solution is IN PROGRESS and so is not binding yet.

This solution requires definition in a GEP of its own to become binding.

**The description included here is intended to illustrate the sort of solution

that an eventual GEP will need to provide, _not to be a binding design.**

Implementations that use Policy objects MUST put a Condition into `status.Conditions`

of any objects affected by a Policy.

That Condition must have a `type` ending in `PolicyAffected` (like

`gateway.networking.k8s.io/PolicyAffected`),

and have the optional `observedGeneration` field kept up to date when the `spec`

of the Policy-attached object changes.

Implementations _should_ use their own unique domain prefix for this Condition

`type` - it is recommended that implementations use the same domain as in the

`controllerName` field on GatewayClass (or some other implementation-unique

domain for implementations that do not use GatewayClass).)

For objects that do _not_ have a `status.Conditions` field available (`Secret`

is a good example), that object MUST instead have an annotation of

`gateway.networking.k8s.io/PolicyAffected: true` (or with an

implementation-specific domain prefix) added instead.

##### Design Considerations

The intent here is to add at least a breadcrumb that leads object owners to have

some way to know that their object is being affected by another object, while

minimizing the number of updates necessary.

Minimizing the object updates is done by only having an update be necessary when

the affected object starts or stops being affected by a Policy, rather than if

the Policy itself has been updated.

There is already a similar Condition to be placed on _Policy_ objects, rather

than on the _targeted_ objects, so this solution is also being included in the

Condiions section below.

#### GatewayClass status Extension Types listing

Support: Provisional

This solution is IN PROGRESS, and so is not binding yet.

Each implementation MUST list all relevant CRDs in its GatewayClass status (like

Policy, and other extension types, like paramsRef targets, filters, and so on).

This is going to be tracked in its own GEP, https://github.com/kubernetes-sigs/gateway-api/discussions/2118

is the initial discussion. This document will be updated with the details once

that GEP is opened.

##### Design Considerations

This solution:

- is low cost in terms of apiserver updates (because it's only on the GatewayClass,

and only on implementation startup)

- provides a standard place for all users to look for relevant objects

- ties in to the Conformance Profiles design and other efforts about GatewayClass

status

#### Standard status stanza

Support: Provisional

This solution is IN PROGRESS and so is not binding yet.

This solution requires definition in a GEP of its own to become binding.

**The description included here is intended to illustrate the sort of solution

that an eventual GEP will need to provide, _not to be a binding design. THIS IS

AN EXPERIMENTAL SOLUTION DO NOT USE THIS YET.**

An implementation SHOULD include the name, namespace, apiGroup and Kind of Policies

affecting an object in the new `effectivePolicy` status stanza on Gateway API

objects.

This stanza looks like this:

```yaml

kind: Gateway

...

status:

effectivePolicy:

- name: some-policy

namespace: some-namespace

apiGroup: implementation.io

kind: AwesomePolicy

...

```

##### Design Considerations

This solution is designed to limit the number of status updates required by an

implementation to when a Policy starts or stops being relevant for an object,

rather than if that Policy's settings are updated.

It helps a lot with discoverability, but comes at the cost of a reasonably high

fanout cost. Implementations using this solution should ensure that status updates

are deduplicated and only sent to the apiserver when absolutely necessary.

Ideally, these status updates SHOULD be in a separate, lower-priority queue than

other status updates or similar solution.

#### PolicyBinding resource

Support: Provisional

This solution is IN PROGRESS and so is not binding yet.

This solution requires definition in a GEP of its own to become binding.

**The description included here is intended to illustrate the sort of solution

that the eventual GEP will need to provide, _not to be a binding design. THIS IS

AN EXPERIMENTAL SOLUTION DO NOT USE THIS YET.**

Implementations SHOULD create an instance of a new `gateway.networking.k8s.io/EffectivePolicy`

object when one or more Policy objects become relevant to the target object.

The `EffectivePolicy` object MUST be in the same namespace as the object targeted

by the Policy, and must have the _same name_ as the object targeted like the Policy.

This is intended to mirror the Services/Endpoints naming convention, to allow for

ease of discovery.

The `EffectivePolicy` object MUST set the following information:

- The name, namespace, apiGroup and Kind of Policy objects affecting the targeted

object.

- The full resultant set of Policy affecting the targeted object.

The above details MUST be namespaced using the `controllerName` of the implementation

(could also be by GatewayClass), similar to Route status being namespaced by

`parentRef`.

An example `EffectivePolicy` object is included here - this may be superseded by

a later GEP and should be updated or removed in that case. Note that it does

_not_ contain a `spec` and a `status` stanza - by definition this object _only_

contains `status` information.

```yaml

kind: EffectivePolicy

apiVersion: gateway.networkking.k8s.io/v1alpha2

metadata:

name: targeted-object

namespace: targeted-object-namespace

policies:

- controllerName: implementation.io/ControllerName

objects:

- name: some-policy

namespace: some-namespace

apiGroup: implementation.io

kind: AwesomePolicy

resultantPolicy:

awesomePolicy:

configitem1:

defaults:

foo: 1

overrides:

bar: important-setting

```

Note here that the `resultantPolicy` setting is defined using the same mechanisms

as an `unstructured.Unstructured` object in the Kubernetes Go libraries - it's

effectively a `map[string]struct{}` that is stored as a `map[string]string` -

which allows an arbitrary object to be specified there.

Users or tools reading the config underneath `resultantPolicy` SHOULD display

it in its encoded form, and not try to deserialize it in any way.

The rendered YAML MUST be usable as the `spec` for the type given.

##### Design considerations

This will provide _full_ visibility to end users of the _actual settings_ being

applied to their object, which is a big discoverability win.

However, it relies on the establishment and communication of a convention ("An

EffectivePolicy is right next to your affected object"), that may not be desirable.

Thus its status as EXPERIMENTAL DO NOT USE YET.

#### Validating Admission Controller to inform users about relevant Policy

Implementations MAY supply a Validating Admission Webhook that will return a

WARNING message when an applied object is affected by some Policy, which may be

an inherited or indirect one.

The warning message MAY include the name, namespace, apiGroup and Kind of relevant

Policy objects.

##### Design Considerations

Pro:

- This gives object owners a very clear signal that something some Policy is

going to affect their object, at apply time, which helps a lot with discoverability.

Cons:

- Implementations would have to have a webhook, which is another thing to run.

- The webhook will need to have the same data model that the implementation uses,

and keep track of which GatewayClasses, Gateways, Routes, and Policies are

relevant. Experience suggests this will not be a trivial engineering exercise,and will add a lot of implementation complexity.

#### `kubectl` plugin or command-line tool

To help improve UX and standardization, a kubectl plugin will be developed that

will be capable of describing the computed sum of policy that applies to a given

resource, including policies applied to parent resources.

Each Policy CRD that wants to be supported by this plugin will need to follow

the API structure defined above and add a `gateway.networking.k8s.io/policy: true`

label to the CRD.

### Conditions

Implementations using Policy objects MUST include a `spec` and `status` stanza, and the `status` stanza MUST contain a `conditions` stanza, using the standard Condition format.

Policy authors should consider namespacing the `conditions` stanza with a

`controllerName`, as in Route status, if more than one implementation will be

reconciling the Policy type.

#### On `Policy` objects

Controllers using the Gateway API policy attachment model MUST populate the

`Accepted` condition and reasons as defined below on policy resources to provide

a consistent experience across implementations.

```go

// PolicyConditionType is a type of condition for a policy.

type PolicyConditionType string

// PolicyConditionReason is a reason for a policy condition.

type PolicyConditionReason string

const (

// PolicyConditionAccepted indicates whether the policy has been accepted or rejected

// by a targeted resource, and why.

//

// Possible reasons for this condition to be True are:

//

// * "Accepted"

//

// Possible reasons for this condition to be False are:

//

// * "Conflicted"

// * "Invalid"

// * "TargetNotFound"

//

PolicyConditionAccepted PolicyConditionType = "Accepted"

// PolicyReasonAccepted is used with the "Accepted" condition when the policy has been

// accepted by the targeted resource.

PolicyReasonAccepted PolicyConditionReason = "Accepted"

// PolicyReasonConflicted is used with the "Accepted" condition when the policy has not

// been accepted by a targeted resource because there is another policy that targets the same

// resource and a merge is not possible.

PolicyReasonConflicted PolicyConditionReason = "Conflicted"

// PolicyReasonInvalid is used with the "Accepted" condition when the policy is syntactically

// or semantically invalid.

PolicyReasonInvalid PolicyConditionReason = "Invalid"

// PolicyReasonTargetNotFound is used with the "Accepted" condition when the policy is attached to

// an invalid target resource

PolicyReasonTargetNotFound PolicyConditionReason = "TargetNotFound"

)

```

#### On targeted resources

(copied from [Standard Status Condition][#standard-status-condition])

This solution requires definition in a GEP of its own to become binding.

**The description included here is intended to illustrate the sort of solution

that an eventual GEP will need to provide, _not to be a binding design.**

Implementations that use Policy objects MUST put a Condition into `status.Conditions`

of any objects affected by a Policy.

That Condition must have a `type` ending in `PolicyAffected` (like

`gateway.networking.k8s.io/PolicyAffected`),

and have the optional `observedGeneration` field kept up to date when the `spec`

of the Policy-attached object changes.

Implementations _should_ use their own unique domain prefix for this Condition

`type` - it is recommended that implementations use the same domain as in the

`controllerName` field on GatewayClass (or some other implementation-unique

domain for implementations that do not use GatewayClass).)

For objects that do _not_ have a `status.Conditions` field available (`Secret`

is a good example), that object MUST instead have an annotation of

`gateway.networking.k8s.io/PolicyAffected: true` (or with an

implementation-specific domain prefix) added instead.

### Interaction with Custom Filters and other extension points

There are multiple methods of custom extension in the Gateway API. Policy

attachment and custom Route filters are two of these. Policy attachment is

designed to provide arbitrary configuration fields that decorate Gateway API

resources. Route filters provide custom request/response filters embedded inside

Route resources. Both are extension methods for fields that cannot easily be

standardized as core or extended fields of the Gateway API. The following

guidance should be considered when introducing a custom field into any Gateway

controller implementation:

1. For any given field that a Gateway controller implementation needs, the

possibility of using core or extended should always be considered before

using custom policy resources. This is encouraged to promote standardization

and, over time, to absorb capabilities into the API as first class fields,

which offer a more streamlined UX than custom policy attachment.

2. Although it's possible that arbitrary fields could be supported by custom

policy, custom route filters, and core/extended fields concurrently, it is

recommended that implementations only use multiple mechanisms for

representing the same fields when those fields really _need_ the defaulting

and/or overriding behavior that Policy Attachment provides. For example, a

custom filter that allowed the configuration of Authentication inside a

HTTPRoute object might also have an associated Policy resource that allowed

the filter's settings to be defaulted or overridden. It should be noted that

doing this in the absence of a solution to the status problem is likely to

be *very* difficult to troubleshoot.

### Conformance Level

This policy attachment pattern is associated with an "EXTENDED" conformance

level. The implementations that support this policy attachment model will have

the same behavior and semantics, although they may not be able to support

attachment of all types of policy at all potential attachment points.

### Apply Policies to Sections of a Resource

Policies can target specific matches within nested objects. For instance, rather than

applying a policy to the entire Gateway, we may want to attach it to a particular Gateway listener.

To achieve this, an optional `sectionName` field can be set in the `targetRef` of a policy

to refer to a specific listener within the target Gateway.

```yaml

apiVersion: gateway.networking.k8s.io/v1beta1

kind: Gateway

metadata:

name: foo-gateway

spec:

gatewayClassName: foo-lb

listeners:

- name: bar

...

---

apiVersion: networking.acme.io/v1alpha2

kind: AuthenticationPolicy

metadata:

name: foo

spec:

provider:

issuer: "https://oidc.example.com"

targetRef:

name: foo-gateway

group: gateway.networking.k8s.io

kind: Gateway

sectionName: bar

```

The `sectionName` field can also be used to target a specific section of other resources:

* Service.Ports.Name

* xRoute.Rules.Name

For example, the RetryPolicy below applies to a RouteRule inside an HTTPRoute.

```yaml

apiVersion: gateway.networking.k8s.io/v1alpha2

kind: HTTPRoute

metadata:

name: http-app-1

labels:

app: foo

spec:

hostnames:

- "foo.com"

rules:

- name: bar

matches:

- path:

type: Prefix

value: /bar

forwardTo:

- serviceName: my-service1

port: 8080

---

apiVersion: networking.acme.io/v1alpha2

kind: RetryPolicy

metadata:

name: foo

spec:

maxRetries: 5

targetRef:

name: foo

group: gateway.networking.k8s.io

kind: HTTPRoute

sectionName: bar

```

This would require adding a `name` field to those sub-resources that currently lack a name. For example,

a `name` field could be added to the `RouteRule` object:

```go

type RouteRule struct {

// Name is the name of the Route rule. If more than one Route Rule is

// present, each Rule MUST specify a name. The names of Rules MUST be unique

// within a Route.

//

// Support: Core

//

// +kubebuilder:validation:MinLength=1

// +kubebuilder:validation:MaxLength=253

// +optional

Name string `json:"name,omitempty"`

// ...

}

```

If a `sectionName` is specified, but does not exist on the targeted object, the Policy must fail to attach,

and the policy implementation should record a `resolvedRefs` or similar Condition in the Policy's status.

When multiple Policies of the same type target the same object, one with a `sectionName` specified, and one without,

the one with a `sectionName` is more specific, and so will have all its settings apply. The less-specific Policy will

not attach to the target.

Note that the `sectionName` is currently intended to be used only for Direct Policy Attachment when references to

SectionName are actually needed. Inherited Policies are always applied to the entire object.

The `PolicyTargetReferenceWithSectionName` API can be used to apply a direct Policy to a section of an object.

### Advantages

* Incredibly flexible approach that should work well for both ingress and mesh

* Conceptually similar to existing ServicePolicy proposal and BackendPolicy

pattern

* Easy to attach policy to resources we don’t control (Service, ServiceImport,

etc)

* Minimal API changes required

* Simplifies packaging an application for deployment as policy references do not

need to be part of the templating

### Disadvantages

* May be difficult to understand which policies apply to a request

## Examples

This section provides some examples of various types of Policy objects, and how

merging, `defaults`, `overrides`, and other interactions work.

### Direct Policy Attachment

The following Policy sets the minimum TLS version required on a Gateway Listener:

```yaml

apiVersion: networking.example.io/v1alpha1

kind: TLSMinimumVersionPolicy

metadata:

name: minimum12

namespace: appns

spec:

minimumTLSVersion: 1.2

targetRef:

name: internet

group: gateway.networking.k8s.io

kind: Gateway

```

Note that because there is no version controlling the minimum TLS version in the

Gateway `spec`, this is an example of a non-field Policy.

### Inherited Policy Attachment

It also could be useful to be able to _default_ the `minimumTLSVersion` setting

across multiple Gateways.

This version of the above Policy allows this:

```yaml

apiVersion: networking.example.io/v1alpha1

kind: TLSMinimumVersionPolicy

metadata:

name: minimum12

namespace: appns

spec:

defaults:

minimumTLSVersion: 1.2

targetRef:

name: appns

group: ""

kind: namespace

```

This Inherited Policy is using the implicit hierarchy that all resources belong

to a namespace, so attaching a Policy to a namespace means affecting all possible

resources in a namespace. Multiple hierarchies are possible, even within Gateway

API, for example Gateway -> Route, Gateway -> Route -> Backend, Gateway -> Route

-> Service. GAMMA Policies could conceivably use a hierarchy of Service -> Route

as well.

Note that this will not be very discoverable for Gateway owners in the absence of

a solution to the Policy status problem. This is being worked on and this GEP will

be updated once we have a design.

Conceivably, a security or admin team may want to _force_ Gateways to have at least

a minimum TLS version of `1.2` - that would be a job for `overrides`, like so:

```yaml

apiVersion: networking.example.io/v1alpha1

kind: TLSMinimumVersionPolicy

metadata:

name: minimum12

namespace: appns

spec:

overrides:

minimumTLSVersion: 1.2

targetRef:

name: appns

group: ""

kind: namespace

```

This will make it so that _all Gateways_ in the `default` namespace _must_ use

a minimum TLS version of `1.2`, and this _cannot_ be changed by Gateway owners.

Only the Policy owner can change this Policy.

### Handling non-scalar values

In this example, we will assume that at some future point, HTTPRoute has grown

fields to configure retries, including a field called `retryOn` that reflects

the HTTP status codes that should be retried. The _value_ of this field is a

list of strings, being the HTTP codes that must be retried. The `retryOn` field

has no defaults in the field definitions (which is probably a bad design, but we

need to show this interaction somehow!)

We also assume that a Inherited `RetryOnPolicy` exists that allows both

defaulting and overriding of the `retryOn` field.

A full `RetryOnPolicy` to default the field to the codes `501`, `502`, and `503`

would look like this:

```yaml

apiVersion: networking.example.io/v1alpha1

kind: RetryOnPolicy

metadata:

name: retryon5xx

namespace: appns

spec:

defaults:

retryOn:

- "501"

- "502"

- "503"

targetRef:

kind: Gateway

group: gateway.networking.k8s.io

name: we-love-retries

```

This means that, for HTTPRoutes that do _NOT_ explicitly set this field to something

else, (in other words, they contain an empty list), then the field will be set to

a list containing `501`, `502`, and `503`. (Notably, because of Go zero values, this

would also occur if the user explicitly set the value to the empty list.)

However, if a HTTPRoute owner sets any value other than the empty list, then that

value will remain, and the Policy will have _no effect_. These values are _not_

merged.

If the Policy used `overrides` instead:

```yaml

apiVersion: networking.example.io/v1alpha1

kind: RetryOnPolicy

metadata:

name: retryon5xx

namespace: appns

spec:

overrides:

retryOn:

- "501"

- "502"

- "503"

targetRef:

kind: Gateway

group: gateway.networking.k8s.io

name: you-must-retry

```

Then no matter what the value is in the HTTPRoute, it will be set to `501`, `502`,

`503` by the Policy override.

### Interactions between defaults, overrides, and field values

All HTTPRoutes that attach to the `YouMustRetry` Gateway will have any value

_overwritten_ by this policy. The empty list, or any number of values, will all

be replaced with `501`, `502`, and `503`.

Now, let's also assume that we use the Namespace -> Gateway hierarchy on top of

the Gateway -> HTTPRoute hierarchy, and allow attaching a `RetryOnPolicy` to a

_namespace_. The expectation here is that this will affect all Gateways in a namespace

and all HTTPRoutes that attach to those Gateways. (Note that the HTTPRoutes

themselves may not necessarily be in the same namespace though.)

If we apply the default policy from earlier to the namespace:

```yaml

apiVersion: networking.example.io/v1alpha1

kind: RetryOnPolicy

metadata:

name: retryon5xx

namespace: appns

spec:

defaults:

retryOn:

- "501"

- "502"

- "503"

targetRef:

kind: Namespace

group: ""

name: appns

```

Then this will have the same effect as applying that Policy to every Gateway in

the `default` namespace - namely that every HTTPRoute that attaches to every

Gateway will have its `retryOn` field set to `501`, `502`, `503`, _if_ there is no

other setting in the HTTPRoute itself.

With two layers in the hierarchy, we have a more complicated set of interactions

possible.

Let's look at some tables for a particular HTTPRoute, assuming that it does _not_

configure the `retryOn` field, for various types of Policy at different levels.

#### Overrides interacting with defaults for RetryOnPolicy, empty list in HTTPRoute

||None|Namespace override|Gateway override|HTTPRoute override|

|----|-----|-----|----|----|

|No default|Empty list|Namespace override| Gateway override Policy| HTTPRoute override|

|Namespace default| Namespace default| Namespace override | Gateway override | HTTPRoute override |

|Gateway default| Gateway default | Namespace override | Gateway override | HTTPRoute override |

|HTTPRoute default| HTTPRoute default | Namespace override | Gateway override | HTTPRoute override|

#### Overrides interacting with other overrides for RetryOnPolicy, empty list in HTTPRoute

||No override|Namespace override A|Gateway override A|HTTPRoute override A|

|----|-----|-----|----|----|

|No override|Empty list|Namespace override| Gateway override| HTTPRoute override|

|Namespace override B| Namespace override B| Namespace override

first created wins

otherwise first alphabetically | Namespace override B | Namespace override B|

|Gateway override B| Gateway override B | Namespace override A| Gateway override

first created wins

otherwise first alphabetically | Gateway override B|

|HTTPRoute override B| HTTPRoute override B | Namespace override A| Gateway override A| HTTPRoute override

first created wins

otherwise first alphabetically|

#### Defaults interacting with other defaults for RetryOnPolicy, empty list in HTTPRoute

||No default|Namespace default A|Gateway default A|HTTPRoute default A|

|----|-----|-----|----|----|

|No default|Empty list|Namespace default| Gateway default| HTTPRoute default A|

|Namespace default B| Namespace default B| Namespace default

first created wins

otherwise first alphabetically | Gateway default A | HTTPRoute default A|

|Gateway default B| Gateway default B| Gateway default B| Gateway default

first created wins

otherwise first alphabetically | HTTPRoute default A|

|HTTPRoute default B| HTTPRoute default B| HTTPRoute default B| HTTPRoute default B| HTTPRoute default

first created wins

otherwise first alphabetically|

Now, if the HTTPRoute _does_ specify a RetryPolicy,

it's a bit easier, because we can basically disregard all defaults:

#### Overrides interacting with defaults for RetryOnPolicy, value in HTTPRoute

||None|Namespace override|Gateway override|HTTPRoute override|

|----|-----|-----|----|----|

|No default| Value in HTTPRoute|Namespace override| Gateway override | HTTPRoute override|

|Namespace default| Value in HTTPRoute| Namespace override | Gateway override | HTTPRoute override |

|Gateway default| Value in HTTPRoute | Namespace override | Gateway override | HTTPRoute override |

|HTTPRoute default| Value in HTTPRoute | Namespace override | Gateway override | HTTPRoute override|

#### Overrides interacting with other overrides for RetryOnPolicy, value in HTTPRoute

||No override|Namespace override A|Gateway override A|HTTPRoute override A|

|----|-----|-----|----|----|

|No override|Value in HTTPRoute|Namespace override A| Gateway override A| HTTPRoute override A|

|Namespace override B| Namespace override B| Namespace override

first created wins

otherwise first alphabetically | Namespace override B| Namespace override B|

|Gateway override B| Gateway override B| Namespace override A| Gateway override

first created wins

otherwise first alphabetically | Gateway override B|

|HTTPRoute override B| HTTPRoute override B | Namespace override A| Gateway override A| HTTPRoute override

first created wins

otherwise first alphabetically|

#### Defaults interacting with other defaults for RetryOnPolicy, value in HTTPRoute

||No default|Namespace default A|Gateway default A|HTTPRoute default A|

|----|-----|-----|----|----|

|No default|Value in HTTPRoute|Value in HTTPRoute|Value in HTTPRoute|Value in HTTPRoute|

|Namespace default B|Value in HTTPRoute|Value in HTTPRoute|Value in HTTPRoute|Value in HTTPRoute|

|Gateway default B|Value in HTTPRoute|Value in HTTPRoute|Value in HTTPRoute|Value in HTTPRoute|

|HTTPRoute default B|Value in HTTPRoute|Value in HTTPRoute|Value in HTTPRoute|Value in HTTPRoute|

## Removing BackendPolicy

BackendPolicy represented the initial attempt to cover policy attachment for

Gateway API. Although this proposal ended up with a similar structure to

BackendPolicy, it is not clear that we ever found sufficient value or use cases